Seeing Like a City, At Least Some of the Time

On Wichita's finally approved parking plan, and other public goods

Years ago, the Canadian urbanist and political theorist (a label which I suppose gives at least some critics of paid parking in Wichita no less than three distinct reasons to automatically dismiss his comments) Warren Magnusson wrote Politics of Urbanism: Seeing Like a City, an excellent work of philosophy, history, and urban politics. Early in the book, he stated his thesis bluntly: “to see like a city is to grow up politically.” By “seeing like a city” he meant 1) looking at the problems and opportunities which come from people living alongside one another with an eye towards maintaining public goods and 2) embracing ad hoc responses to those problems and opportunities which reflect the organic, always-changing, and non-sovereign character of city life. By “growing up politically” he meant, simply, maturity: accepting unavoidable costs, embracing the good instead of the perfect, and shouldering the sort of responsibility which refuses delay decisions indefinitely.

This past Tuesday, after months of debate both public and behind the scenes, Wichita’s city council grew up and did an unpopular thing: it instituted a system of paid parking in parts of our downtown, and in so doing set up a plan that, at least in theory, will start responsibly addressing the costs and requirements of the public good which is having well-maintained places to park in our urban core. I applaud them for doing so, especially since I thought there were likely to be four votes out of the seven members of the council to kick the issue down the road yet again. Instead they did good—they saw, in however qualified a way, our city for what it is.

What is our city? In the minds of some—as I discussed at length in a previous piece on the paid parking debate I wrote back in September—Wichita isn’t the sort of city whose shoppers, owners, commuters, landlords, renters, workers, or really anyone who lives here, can possibly handle any sort of change in the profoundly subsidized, profoundly suburbanized model which characterizes the city’s look and flow. At the marathon meeting on Tuesday, more than a few of those giving public comments fell back on these constant refrains: Wichitans are too cheap to pay for parking, and Wichita can’t be compared to those cities (many of which are right here in Kansas, and are smaller than Wichita to boot!) where the residents aren’t too cheap to recognize the value of maintaining one of central components of the good that is a thriving downtown. My greatest respect are for those business owners and others who were willing to push back on this too-common assumption: that Wichita, the 50th-largest city in the country, actually is too small, or too small-minded, to handle the sort of affordably priced parking meters that you can find practically everywhere else.

To be fair, others aren’t so much locked into this small and suburban model of city life as they are convinced—with, unfortunately, good if not sufficient reason—that any attempt to organize and monetize downtown’s open spaces for the sake of managing a public good like parking is inextricable from corrupt deals and irresponsible decisions, and therefore not worth doing. No one has done more locally to shine a light on the too-frequent corruption and irresponsibility of past (and some present) decision-makers in Wichita’s government than the journalist Dion Lefler, and the hard questions he’s asked and the patterns of failure he’s uncovered—particularly when it comes to actually requiring business interests to pay the fees and costs they’re contracts with the city supposedly require them to do—deserve applause as well.

But frustratingly, for Lefler and others who have long and correctly demanded reform from our city government the only appropriate response to all this is to impose static expectations upon the city: nothing should be done about parking until all the information has been obtained and audited about every downtown business contract and every unpaid bill. If Wichita were governed by a democratic legislature that wielded plenary (and thus sovereign) power over all financial transactions, property ownership, and income generation within its city boundaries, I can imagine the reasonableness of regularly insisting upon that kind of fiscal finality. But American cities, operating in a world which Dillon’s Rule built, by necessity need to lean into their own organic complexity, recognizing that the dozens of businesses and groups and factions which municipal governments confront regularly are all going to pursue ends and follow trajectories which don’t align with the rules laid down by the city council. In other words, and to specifically refer to the $13 million which Old Town businesses in Wichita have failed to pay into the parking fund over the past quarter-century: how are you going to make them pay? Since the city doesn’t have the legal authority to simply capture a percentage of their profits or rents through direct transfers, how much should the city budget for litigation costs as businesses and property-owners point to all the pass-alongs and changes in ownership over the years as they fight to maintain their current operating budgets? Brandon Johnson (still a valuable, practical voice on the city council) was right in saying from the dais during the meeting that this plan isn’t ideal, but that refusing to support it because of its lack of ideal-ness is hardly the right way to see the way forward when facing Wichita’s challenges.

Maybe the central issue is exactly what you see those challenges as. If the purpose of managing downtown parking is simply to make sure sufficient funds are deposited into the operation and maintenance of downtown parking, then Lefler’s sharp response would be on point: “make the businesses pay what they’re supposed to pay and the parking problem goes away.” Again, more than a few of those who spoke at the lengthy Tuesday city council meeting viewed Wichita in more or less exactly that way: not as a complex organism what needs to find a way to either collectively promote or enable groups of residents to effectively attend to common goods, but as a loose association of consumers, buyers, and sellers, a conglomeration of individuals who want all transactions to be reliable and cheap. (Frankly, I see this as the same mentality which contributed to the council’s sad decision at the conclusion of the same Tuesday meeting to strengthen the “efficiency” of the city when it comes to addressing the “inconveniences” of Wichta’s homeless population, though thankfully organized dissent helped mitigate the worst elements of that new ordinance.)

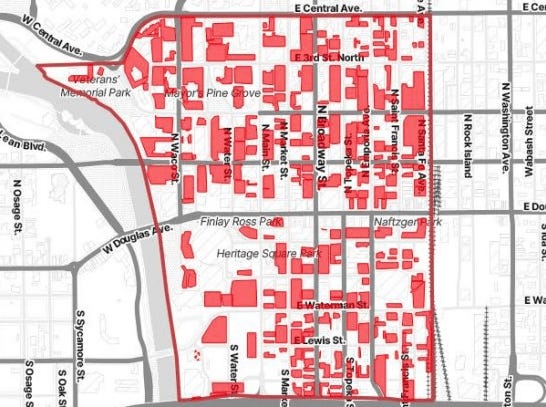

But that attitude is simply incorrect. The point of managing the public good of parking, including compromising on a plan that will allow collective economic responsibility for that public good to be shared by all who use it, isn’t just to maintain the cleanliness of parking spots, anymore than it us just to make certain the few crowded parking areas downtown finally see some regular overturn. Rather, it is to slowly start moving Wichita—long past when they should have started moving!—towards a recognition of the warped development pattern within the city core, and nudging those hundreds of decision-makers throughout the downtown who are thinking about whether or not to relocate, or to invest in or sell off private parking, or to set or change rates for residents or renters, to go about that thinking more intentionally. At present, our broken, effectively non-existent, “plan” for parking as given us this:

Wichita’s tremendously overbuilt infrastructure means, practically speaking, that for people with at least limited mobility, there will always be sufficient parking for just about anywhere they need to get downtown, and a lot of it will remain free. And the plan that the city voted to accept does explicitly include requirements of additional free parking when it comes to handicapped spaces, rideshare spaces, and more. I can understand those who think—oh, Wichita’s has empty lots and businesses going under? Obviously, it therefore would be crazy to expect anyone to pay for any of it! But again, that hearkens back to the same rationality which ignores the civc component to this discussion, the fact that people living in proximity to each other, organically associating with each other, will not always need to or want to maxmize their choices in the same way. Making the good of parking economically meaningful (including by putting a price on it) is not the only way to get those who live and work and operate within a municipal space to start prioritizing public goods differently—but it is a method worth embracing, especially since it can accomplish other fiscal needs along the way.

I hope all this hasn’t made me come off as a complete apologist for how the city council and the staff which has worked for years on this problem have done their jobs and cast their votes. I’m not! The plan itself is jerry-rigged in ways that are clearly political; Lefler, whatever my disagreements with him on this point, isn’t wrong in seeing the exclusion of the Delano neighborhood from the plan as a give-away. Likewise the fact that this entirely process has been conducted in light of an obligation to an outside corporation, the Idaho-based Car Park, rather than planning to make use of actual city employees as ought to have been the case, is a massive (and arguably quite undemocratic) frustration. The fact that Old Town will have the option of creating a sales tax-based community-improvement-district (CID) to generate the funds they’re determined to owe the city (on the basis of the arbitrarily determined $15 per space per month, a full $10 less than what some of the ignored contracts dating back to the 1990s said they should have been paying by now), rather than making use of the same mix of meters and timed-parking which the rest of the urban core will be required to use, simply because of the particulars of the Self-Sustaining Municipal Improvement District (SSMID) which the Wichita Downtown Development Corporation invented in 2010, is also likely to cause all sorts of problems down the road. And as for the final votes, whatever their conflicted motivations, I have appreciation for Councilmembers Ballard, Glasscock, Johnson, Johnston, and Tuttle for seeing things clearly. But when it comes to the no votes: while Mayor Lily Wu rightly challenged City Manager Robert Layton about the revelation of the $13 million uncollected dollars from unenforced contracts, and deserves credit for doing so, she should have gone further (she should have asked him why he shouldn’t resign when confronted with such a huge oversight), and her consequent vote against the final plan—one that she knew would pass—seems to me at least as much a matter of pique as principle. Councilmember Hoheisel, while he should have voted for it too, at least had the more reasonable argument that he didn’t want to vote for a plan that would require the city to simply assume all the existing maintenance costs out of the general budget, even though he knew there was no viable plan available that could have passed that quarter-century worth of costs back to businesses supposedly responsible for it, for all the aforementioned reasons.

Thanks for five people who maturely saw things as I think they needed to be seen, Wichita is going to start being, in 2025, a little bit more of the city it ought to be. That doesn’t cover up all the ways it remains anything but that. But here at the end of the politically distressing year of 2024, the fact that a workable plan emerged from these months (years!) of wrangling speaks well for my city, a place that, sometimes anyway, seems like it might actually grow into being a city that is responsible to its own slow-growth, mid-sized, way of thriving. This vote was a good step in that direction, the first really good one in a while, I think.