"Practical" Developers, "Idealistic" Planners, and Their Disagreements (Some of the Time)

The enduring question of embracing high principles vs. accepting current practices, plus the problem of automobile-centric intersections, part infinity

[Cross-posted to Wichita Story]

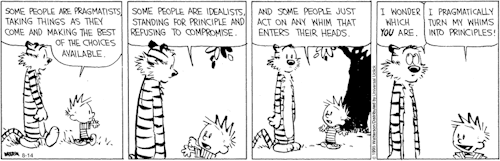

The tension between acting in accordance with one’s ethical or moral principles versus contenting oneself with pragmatic efficiency and “realism” is one of the oldest tensions in the whole history of philosophy. It’s an old and abiding tension in part because one can experience it everywhere. Here in Wichita, KS, I’ve lately been thinking about primarily in connection with an intersection a little over a mile from my house, where the major arterial streets Central and Ridge meet. (Allow me a long and very localized digression here; I’ll get back to my main point presently.)

This is not, by any possible stretch of the imagination, a pleasantly walkable intersection, nor a location with much of any kind of real artistic activity, localized commerce, or civic engagement. It’s a stretch of two “stroads,” to use a Strong Towns term. These are streets that are surrounded on all sides with various forms of human habitation, single-family homes and apartments complexes and more, and which therefore ought to be areas of organic commerce and social interaction, but have instead long since been overtaken by the automobile-centric road mentality: got to make things as wide, as structured, and as efficient as possible, because that enables (and, of course, encourages) speed, and people HATE not being able to get from point A to point B as quickly as possible. American cities have overwhelmingly accepted that imperative as a ruling one, Wichita certainly included. As a result, the sorts of opportunities for commerce and “street life” along Central and Ridge in west Wichita are predictable: banks, gas stations, discount stores, and whatever else can hold onto some parking until they go out of business. Locations that actually generate neighborhood-building social capital, along with money, they are definitely not.

For all that, it is an intersection I know relatively well, because I bike along Central all the time; sometimes when I want to make a straight shot east towards Wichita’s downtown, or sometimes when I’m biking to the west side’s farmers market and bike lane connections at Sedgwick County Park. I don’t have any illusions about the pedestrian- or bicycle-friendliness of this intersection or of the arterial corridors which feed into it; they are dangerous places. Even putting in a nicely designed flashing signal less than a half-mile west of the intersection along a designated “bicycle boulevard” hasn’t prevented terrible pedestrian accidents along this route. Still, when you have most of these stretches of road, in all four directions from the intersection, filled with housing and people—people who will want to move and not always do so solely in their automobiles—that’s going to conflict with the “stroadish” designs which dominate here.

Though it was probably just a result of studying growth and density patterns and local development history, I’d like to believe that it was also an awareness of the aforementioned conflict which led to this intersection, along with 17 other locations around Wichita’s “Established Central Area,” to be identified in our city’s Places for People Plan as a “Community Core” node which requires, and discourages, certain development practices. Places for People is a wide-ranging set of planning guides, investment strategies, and zoning recommendations, hammered out through years of meetings and studies, and formally embraced by the city of Wichita in 2019. For a near-entirely automobile-centric, suburban-model, and low-density city like mine, its passage was one of the most encouraging signs of Wichita’s willingness to respond to the difficult realities we are collectively facing that I’ve seen in all 17 years I’ve lived here. It spells out the need Wichita has to control sprawl, incentivize infill construction, attend to climate realities, limit exclusionary zoning, promote affordable housing options, recognize transportation alternatives, and more. Insofar as the intersection of Central and Ridge is concerned, Places for People identified it as a site which needs “redevelopment that is contextual to the [in this case, multi-family residential and small-scale commercial] environment in which it is occurring.” The fact that the intersection had been designed with at least some acknowledgment of walkability in mind, with the southwest corner including a tiny sunken path with benches (neither of which I have ever seen used, but one can always hope!), suggests that, as implausible as it may seem when you take in the whole location, people who actually know this space well, as I do, can and should imagine some kind of post-stroad possibilities here.

But instead, on the northeast corner, we’re going to get a new used auto dealership. Not really a development that incentivizes walkability or local commerce, obviously. I would be lying if I said I was broken up over this; I’m not, not really; it’s not like my hopes were high. But still, they existed. And the fact that we’re going get a development that will make imagining a beginning for some kind of principled design difference at this intersection even more unlikely exposes the difficulty of adhering to principles when making policy decisions, and presents a challenge as to why anyone should bother elucidating hopeful principles in the first place.

The northeast corner of Central and Ridge was long occupied by the empty shell of a gas station and car wash which had since gone out of business. Directly north of it you have some low-cost apartments, and across the street from them you have single-family homes. Yes, it’s surely been mildly depressing to those who live in those places to have had an empty—and, as construction has slowly, inconsistently begun, increasingly muddy—lot take up that corner:

But nonetheless, just what is the point of even having a set of policy stipulations and priorities if those in charge of implementing them are going to respond with development proposals from businesses with simply pushing the principle-based objections aside?

That makes it sound more dismissive than it actually was, and I don’t want to be unfair to a bunch of folks whom I have every reason to believe are doing their jobs to the best of their ability. But look: the Wichita’s Metropolitan Area Planning Department considered the proposed development, looked at the site, and came to the obvious conclusion: because the proposed business would not “capitalize on existing multi-family residential and transit service” and would likely “set a precedent for approvals of future applications of this kind….[a] vehicles sales lot [in this location] is not in conformance with the principles of the Places for People Plan.” I’ve talked with city planners here in Wichita who are deeply familiar with and sympathetic to the work of the MAPD, in particular their need to provide the best interpretation PfP they can in light of other existing investment plans and the existing infrastructure at various Community Nodes. I recognize that the Established Central Area which the PfP encompasses is massive and the range of nodes it has established for prioritizing infill development is probably unrealistic. But all that being said: if the argument is that the principles of PfP—principles oriented around the desperate fiscal and environmental need Wichita has to at least slow down our reigning presumption that all business development, no matter how auto-centric or socially disincentivizing, is good—can be set aside here, for a used car dealership along stretch of road that already has two others within a mile along Central, then honestly, where in the city might these principles not also be set aside? And if the likely answer is “nowhere,” then why did so many people work so hard in establishing them in the first place?

Wichita’s Metropolitan Area Planning Commission—which can overrule the Department—did so, with one member making the comment that “[t]his property has been vacant for an awful long time,” that “something needs to happen there,” and that “[a]s far as Wichita Places for People Plan, people are going to drive, they’re not going to walk even to go across the street [at this intersection].” Probably so! But in a city so auto-dependent that it has invested hundreds of millions with the sole aim of keeping auto congestion low, and as at least a partial result has essentially no serious traffic trouble, lot of terribly fast drivers, and a terrible record when it comes to bicycle and pedestrian safety, couldn’t you say that about any intersection in Wichita? Basically, my thought is that if you believe in reigning in the sprawl of a city’s footprint, trying to hold its growth to some kind of socially and economically beneficial limits, and obliging those who do the building and deciding in the city to recognize the truth of at least some of the principles which Places for People reflects, you have to start somewhere, right? Unless, that is, you decide not to start at all.

(I tried to make this point when I spoke against the development when it came up for discussion at my councilmember’s district advisory board meeting, where it went before being sent on to the city council for final approval; I should have known that the person taking the minutes wouldn’t know what “stroad” meant, because when the final report was made to the council, the summary concluded “No members of the public spoke in opposition at this public hearing.” In the end, it passed the DAB 6-2; I know one of those who voted against it, and respect him for it; I’d like to believe that the other “no” vote was from my Councilmember Bryan Frye himself, because I know he is familiar with and accepts much of the Strong Towns critique of how things are done in American cities—but given that the plan received final approval from the city council without any dissent, that’s probably not the case.)

Where am I going with all this? Well, in a recent episode of Kevin Klinkenberg’s The Messy city podcast (which I’ve been inspired by before, and which everyone should listen to) Kevin ranted for bit about what I’m talking about here—except he seemed very much on the side of those who are just trying to accept and make the best out of our various Central and Ridge intersections, and expressed his frustrations for those whose idealistic design aspirations get in the way. Let me transcribe the whole thing, because he expresses his point of view very well:

I always come away with the impression…that there are just an awful lot of people in our world who just--I guess if I were a therapist I would say, “You've got to find a way to get comfortable and with, and love, American cities and towns.” I have been a long-time critic of what we have done to our cities and towns in the United States….I have written before that I absolutely adore a lot of the cities and towns that I encounter in other countries….[T]he cities in the Netherlands are probably close to an ideal that I would personally enjoy and that I think are amazing cities for raising children. I wish we had a built environment that was like that. I make no bones about it. I love those kinds of places, and I wish that was more common. But it's not!

Our cities and our culture is different in this country, and there actually is…a lot of great things that we can focus on that are part of our culture and the way we built cities and towns. One of the things that we have a ton of amnesia about…is that we really did build a lot of amazing cities and towns…from the colonial days all the way up through the 1920s. We had remarkable cities that were very walkable, that had functioning transit systems--that were, by the way, privately owned and maintained….Biking was actually a big deal in the early decades of the 20th century in American cities and towns; it was a very common way to get around. We had these wonderful functional neighborhoods with small entrepreneurs everywhere, small neighborhood grocers. You really had local economies…even in big cities….We had so much of that already in this country.

We've forgotten that; we've lost a lot of it. In the rush to build the new modern city--starting really in the 1920s, but not really kicking off in mass until after World War II--we forgot all about those traditions which we had in this country. So, you know, one aspect of that is that we actually did have…lots of remarkable places. And it's not hard to find, to go to some places where you can find remnants of that all over the country….So that's one thing.

But the other thing is, you know, we have a different culture than almost any other country in the world, and a lot of that is based around a middle-class culture of property ownership. It's very different from so many other places. And it's a good thing. I will just say flat out, it's a good thing. It's one of the things that has kept our country strong. It creates lots of wealth for individuals and families and opportunities for people. And…in our discussions, especially in conversations at conferences, we…my fellow planners and designers and all, have got to find a way to embrace that and love the nature of American cities. Love the nature of…how our cities were platted into individual lots and often into single family detached houses. There's obviously an enormous preference for that in our country, and I just don't think…some of the language we use, which is really critical of that…does any good.

I also think it tends to make us fall into an area where people are just not going to listen….We sometimes take this tack where we come out as opposed to things that are very broadly popular with all kinds of people. And so…I just really feel like as planners and designers, we need to align ourselves with things that are very broadly popular in our society, and then just figure out how do we make the best of it? You know…what are the tweaks we need to make? What are the changes we need to make here and there and be comfortable with the notion of really quality American cities that are different, that are going to be different from cities and other countries.

I know many of you who listen, are, are working every day in that world and are, are trying to make changes, as I am. I think we should all continue to look for ways to make improvements and make incremental progress. But the idea that we're going to have revolutionary change in our society, and all of a sudden, you know, our cities and towns are going to look like European cities and towns, you know, it's just not going to happen. And we delude ourselves by thinking it will happen. It's just not helpful. We need to find a comfort level with what we have, make it the best we can be and learn to really love that and appreciate that. Because I will tell you that most people outside the planning world already do love and appreciate what we have in terms of how our cities are built--or they just don't even think about it very much.

Kevin could, of course, quite legitimately argue that his comments don’t fit with the larger point I’ve been giving an example of here. He might argue—and he wouldn’t be wrong!—that the Places for People Plan here is Wichita isn’t at all revolutionary, that it is entirely incremental, and thus it doesn’t imply any kind of disrespect for the history of American cities or our county’s “middle-class culture of property ownership.” So standing up for enacting, wherever possible, the best judgment of planners who are attempting to nudge our city away from total automobile dominance and towards more walkability might seem like a pragmatic application of principle, not an unrealistic imposition of it. If we read things that way, I don’t disagree with Kevin at all—I’m not a revolutionary myself, however revolutionary some of my political preferences may be, and I’m enough of a small-d democrat to want to see people be able to make local decisions, either directly or through their representatives, which is, after all, what has happened here. So maybe the struggle over Central and Ridge doesn’t reflect any kind of philosophical conflict at all.

Except, that’s not the whole story. For one thing, I don’t think Kevin is correct in claiming that “most people outside the planning world already do love and appreciate what we have in terms of how our cities are built”; if that was so, then from whence comes the constant complaints we’re are all familiar with—and which we often voice ourselves—about underfunded parks, about increasing pollution, about underused and poorly located parking, and so much more? His caveat “they just don't even think about it very much” is much more likely accurate; the great majority of the increasing percentage of the human population that lives in cities almost certainly doesn’t have the time, and resources, or the interest to think structurally about the built environments around them. And as for those who do? Well, a large number follow the political winds which align with their party, their ideology, their convenience, or their remembered experiences from decades past, when only a tiny number of people—troublemakers like Jane Jacobs or Rachel Carson—were warning us about the costs of our built environment. And so they will complain, as some have here in Wichita, about attempts to make alternative forms of transportation safer and thus more of an option. But polling indicates that many others acknowledge—even if they don’t use the language of New Urbanist planners to express it—the insularity of suburbs, the costs of maintenance, and the frustrations of infrastructure overload. If nothing else, Kevin’s conviction that planners need to do a better job of “loving” the overbuilt, sprawling America which actually exists if they want to have any hope of popular support probably needs some qualification.

And also—who is it, exactly, that are acting in the name of ideals, and which ones? Undeniably, Places for People and every similar effort being pursued by city planners everywhere have, at their heart, a set of principles which challenge contemporary construction and development practices in American life. Yet those practices were (and still are—most planners aren’t, after all, Strong Town or New Urbanist types) themselves a product of building interests which adapted to, expanded upon, and became deeply invested in exactly the “new modern city” that Kevin sees as having killed off the smaller, more decentralized, less uniform American-style urbanism which had endured up through World War II. Given the power of those building interests in the politics of American cities, as I discussed before, most of those who were hired by cities to do planning, and most of those educated in architecture and design over the past 80 years anyway, were obliged to respect those development-friendly practices if they wanted to have work. Of course there were always—and always will be—exceptions. But Kevin’s worried concern over a planning profession that wants to challenge the massification of a particular automobile-centric urban style, and by so doing challenge that which has unfortunately, and probably mostly unconsciously, been accepted as normal by the majority of Americans, I think puts the burden of principle in the wrong place. In most of American cities and towns today, it is the legacy of three generations of development-driven planning assumptions, the influence of large-scale developers for whom required parking minimums and ever-further-out subsidized arterial exits are a given, and the desperation of city leaders who have been taught no other language besides growth, that are—intentionally or otherwise—maintaining the core “principles” of our contemporary built environment.

Again, I say all this without any substantive disagreement with Kevin’s primary point: in the same way that Central and Ridge aren’t going to transform into anything other than ugly stroads any time soon, there is good reason for those talking about the future of intersections like Central and Ridge to not condemn those who just want to find some profitable use for the place, under the contrary assumption that some kind of revolution is in the offing. Kevin’s right, in the same way most other defenders of pragmatism throughout the history of philosophy have been right; usually, idealistic revolutions just aren’t in the offing. But I want to be able to continue to insist, wherever and however I can, that that acknowledge should not be taken as argument against pursuing one’s ideals, and holding to one’s principles. In any given particular situation—like here, in this particular planning decision—one might quite judiciously determine that one’s high ideals are counter-productive, and that the PfP principles in question shouldn’t be applied to Central and Ridge. But cases need to be made for taking such exceptions from exhaustively discussed, long hammered-out principles, which in this case are central (however incrementally so!) to Wichita becoming the kind of city I want it (and, fiscally and environmentally speaking, it needs) to be. Given the necessarily organic and interdependent nature of cities, urban design and planning itself can be, and ought to be, subject to serious philosophical critique. But at this moment in American cities, particularly my own, I want to those who default to more commonly accepted practices to have to make an account of themselves, especially when applied principles, however idealistic, attempt to tell them no.

Thanks Russell, and my guess is we are in heated agreement. Two things - first, I think my comments now seem to have been taken not as I intended by more than one person. So that's something I need to work on and clarify. What I had in my had in making those remarks had more to do with our older urban communities (pre-WWII), and how even those are dominated primarily by single-family detached homes. And that's true virtually all over America. The idea that these can all just magically transform into ideal European villages is just silly. I think it would be wise for more folks in our world to learn to love and appreciate our old urbanism for what it is, and embrace its gradual transformation into something that won't be France or Italy. But, it could still be truly wonderful.

Second I'm all for transforming your stroad and the intersection. I've had in my mind for quite some time a short series on what I think a practical approach to sprawl repair can look like, and can actually get done at scale. Again I think most of our fellow urbanists have fantastical ideas about sprawl repair that just aren't helpful. They might look great on a rendering, but there's zero chance it happens. As a born and bred Midwesterner, I just can't let myself promise things to people that have no chance of coming to fruition. It's a character flaw, but there it is. Cheers -