[Still not an essay on the nominal purpose of this substack, but something I have to say anyway.]

I’m awake early this morning, thanks to a headache, after going to bed late last night following 2 ½ hours of talking about yesterday’s terrible news at a local news station, filming comments for their late night and early morning news segments, and I’m thinking about Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount, and also Woody Guthrie’s guitar.

Even without looking at any of the latest news at this pre-dawn moment, I’m relatively confident that one of the dominant political narratives of the coming day—and very likely the coming week at the Republican National Convention, and for that matter perhaps the remaining 4 months of this election cycle and potentially far beyond that as well—will be that the assassination attempt on former President Trump was the indirect (and many will probably say the direct, and who knows?—the investigation to come may prove them correct) result of people calling Donald Trump a fascist, a potential dictator, a threat to democracy. You can’t responsibly go around calling those you politically disagree with your enemies, or enemies of America, or enemies of any particular group or subgroup of Americans, and not be, on some deep level, just wishing for someone to take that talk of enemies seriously, and turn to violence, right?

There’s certainly a truth in that statement, and those of us who think Trump was a terrible president and would (perhaps will) make an even worse one the second time around should not be so blinkered as to deny that truth. But it is not the whole truth, and unless one assumes the human beings are machines that simply respond to the inputs they receive, with no conscious thought, no reflection, no personal judgment whatsoever along the way, a larger truth must be insisted upon. And this is where, perhaps especially because this is Sunday, I get religious. (I owe this particular reflection to the late-last-night comments of my fellow Kansas writer, Joel Mathis.)

The story that has come down to us through the text known as the Book of Matthew has Jesus preaching a sermon, where among many other civilization-changing principles, He is presented as saying in chapter 5, verses 43 through 46 (most famously in the translation found in the King James Version of the Bible):

“Ye have heard that it hath been said, Thou shalt love thy neighbor, and hate thine enemy. But I say unto you, love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you; that ye may be the children of your Father which is in heaven: for he maketh his sun to rise on the evil and on the good, and sendeth rain on the just and on the unjust. For if ye love them which love you, what reward have ye? do not even the publicans the same?”

It is notable, I think, that Jesus is not presented as having said that one’s enemies aren’t actually that—that they are actually your neighbors, actually your fellow human beings, your fellow children of our “Father which is in heaven,” and therefore lovable. No, instead the received text presents Him as saying acknowledging enemies as exactly that: enemies, opponents, those who disagree with and “despitefully use” and even “persecute” those to whom He is speaking (which, for believers like myself, means all of us). He is calling for us to turn away from hate—and thus also, I think it is reasonable to say, violence—when it comes to even those who we see as enemies to that which we hold dear.

This is, in some ways, the most difficult of all Christian teachings. So difficult, you might say, that even the greatest American leaders, even leaders as familiar with the teachings found in the Christian Bible as Abraham Lincoln, chose to lessen its sharpness when confronted with the enormities it implies. In his First Inaugural Address, he insisted as he finished “We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection.” Every political expression must, of course, be guided by a sense of prudence, and articulated in reference to both the aspirations and the reality of the polis that one is speaking of—and, in Lincoln’s case, was trying to save—and so I’ve no criticism of what Lincoln was attempting to rhetorically accomplish at that moment in 1861, when the divisions over the evils of slavery had led to the point of secession and war. But it is nonetheless worth noting that Jesus presented a different possibility: that the affection can and should still exist, even if the bonds which tie people together, which prevent them from seeing one another as an enemy, have been broken.

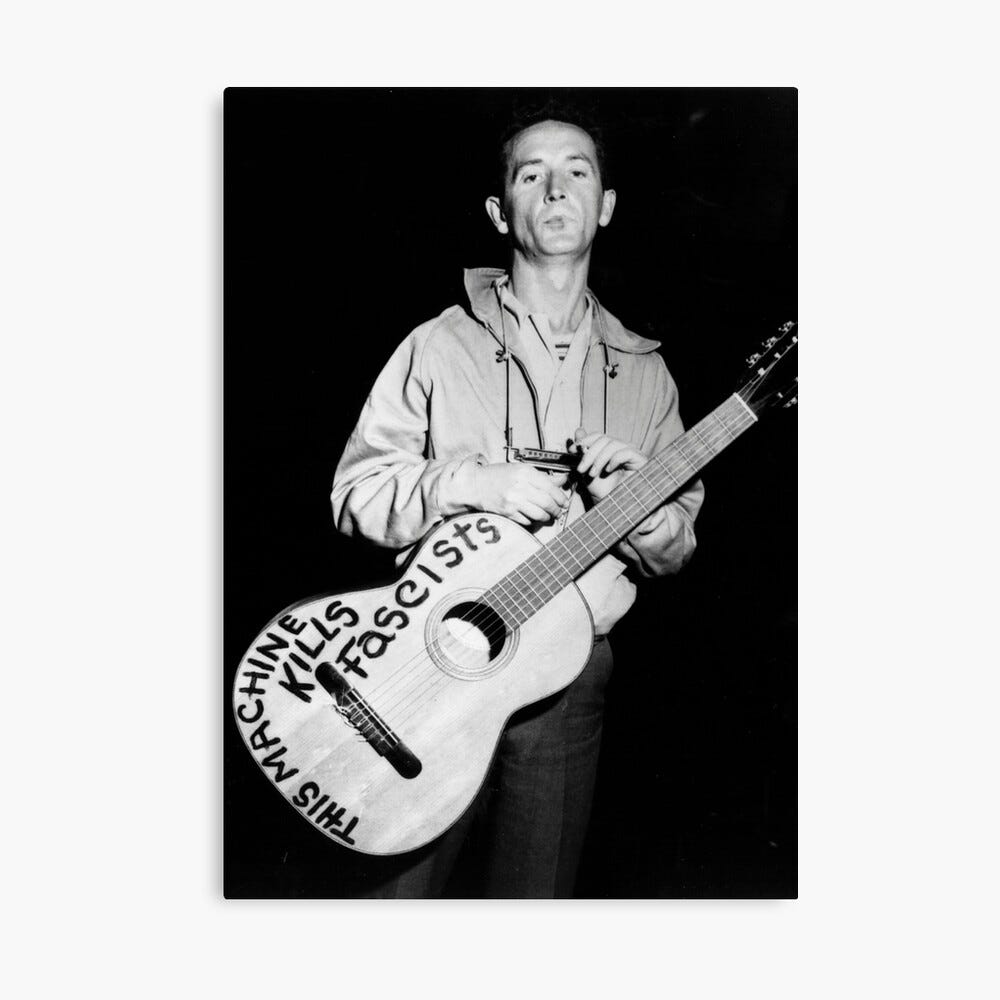

What does that mean, in practice? Well, if worse comes to absolute worse, it may mean pacifism in the face of direct violence, it means showing love even when those being shown love respond with persecution and death. But less than that point, it could mean Woody Guthrie’s condemnation of fascism—with a guitar.

Of course, by the time Guthrie first started writing that message on his guitar, it was 1943, and America’s involvement in the world war against the Nazis of Germany, the fascists of Italy, and the war party which had take control of Japan, had been in full swing for over a year. Yet Guthrie himself connected that message to something much broader than even that global conflict, to a fight that extended back to the Great Depression and the struggle against “economic turmoil and social disintegration” in general. That Guthrie supported the war effort was undeniable. And yet, it remains important I think, that his machine was not a gun, not a weapon, but a musical instrument. A guitar. Which, unless you use it to bash someone over the head, and maybe not even then, can’t kill anyone. But it, and the music it makes, can kill the ideas and movements that make fascists. Who were clearly people that Guthrie regarded as an enemy. He was no pacifist, and made no criticism of soldiers fighting in World War II. Yet still, hold onto that image: the image of fighting fascism with music, not (or at least not only) violence.

As I wrote above, every political action and expression should be guided by prudential judgment: we really should think, as much and as often as we can, about where and when to apply whatever tools and talents we have to promote that which we believe. That’s the churn of participatory democracy, and it’s something I believe in, as both good and wise. It is possible—it’s always possible—that some moment will be revealed as a Rubicon, the crossing of which leaves all conversation and argument and democratic contestation behind and suggests that guitars must be turned into guns. All I can say in the face of that logical point is: resist it, the way Jesus called us to resist it, the way that image of a defiant, guitar-wielding, fascist-“killing” Guthrie resists it. That resistance may, ultimately, be the most prudent, most purely (if naively) democratic action of all.

I’ve been pretty clear that I consider Trump a danger to the flawed but nonetheless real virtues of the flawed but nonetheless still functioning liberal democracy called the United States of America. “Fascist-adjacent” is the term I’ve used, and until and unless Trump himself shares evidence otherwise, I’m going to consider him an authoritarian, or at the very best a quasi-authoritarian threat, to whatever political goods America’s dysfunctional system can still provide. But I’ve also recognized that something similar can be said about practically every American president in my lifetime. That doesn’t wipe away the concern; that doesn’t make me think “oh well, if Johnson and Reagan and Obama were in some ways similar, then clearly our 45th president can’t be all that different, or all that bad.” I can still, and should still, recognize and respond to dangers when I see them. But I won’t respond with violence, and I denounce anyone who does, or who apologizes for such. Violence can’t save us from a political danger—in fact, it can only result in the closing down of the politics that we are trying to save. That’s the message I take this morning from Jesus, and Woody Guthrie (who were probably more similar, in the end, then latter would have ever expected). I pray it’s a message others will take too.

Grateful to call you a (virtual, so far) friend.